Hello!

Much of my attention is on Nepal these days. In the past few weeks, an entire political revolution occurred in the region. Young citizens coordinated online, protested in real life, and replaced the government. The specifics of the revolution are beyond what we do here. However, it is a pressing story about how technology now permeates all aspects of our lives. Especially when it involves economic well-being. A quarter of Nepal’s GDP comes from inbound remittances, which is relevant in the context of what we’ll discuss today.

Today’s story – written in collaboration with the team at Plasma explores what could happen to money if it were as free as the information on the internet. The web, as the word implies, is a network of toolsets that carry information. But our money has not been as connected. Even when stablecoins are involved, offramps and banking regulations add friction to how money moves.

Plasma aims to fix that with an open ecosystem oriented towards aiding developers in building tooling to fix that. Their thesis is that focusing on distribution and unlocking new use-cases in niche markets is the way to “update” money rails for the 21st century.

In today’s issue, I lay out the case for why we need open finance, the role Plasma could play in it, and the nature of applications such innovation could bring to the market.

Long before the television, internet, or blockchains existed, our ports were the original networks that connected the economy. But ships did not have a 0 to 1 moment in a while. Surely, there were steam engines and larger vessels. But the mechanisms of onboarding and offloading items were not standardised. Labour at each port had its own methods of operating. Boxes of goods came in different shapes and sizes. And manufacturing? It entirely depended on how close to the port you were.

In 2009, Venkatesh Rao wrote this stellar review of a book that tracks the evolution of shipping containers. Two numbers that are relevant for our discourse today.

- Shipping containers helped improve the tonnage of ships by 30 times.

- They also made it possible to improve the handling (onboarding and offloading) by a measure of 465 times.

How did this happen? It began in 1956 with a man named Malcolm McLean.

Malcolm McLean stood on the dock at Port Newark, watching nervously as his converted World War II oil tanker, the Ideal X, prepared to depart. Welded to its deck were fifty-eight aluminium boxes, the world’s first shipping containers. Everyone thought he was insane, but he set into motion what would be the standardisation of the shipping industry. We will spare you the details on the regulatory drama, and the incentives ports of the time had against embracing this better model of shipping. Instead, we’ll focus on what Malcolm did.

Malcolm McLean’s genius wasn’t inventing the container; it was understanding that the box alone was worthless without the ecosystem to support it. His first container ship was an elegant solution to a century-old problem: make cargo modular so it can move seamlessly between ships, trucks, and trains. Keep this in mind as we will be thinking about the “ecosystem” in the context of money very soon. First, let’s see what happened to McLean’s innovation.

The idea worked perfectly in theory. In practice, the Ideal X sat idle at most ports. No cranes could lift the containers. No yard infrastructure could store them. Unions refused to handle them. Railroads weren’t built to carry them.

So, McLean did what any sane man would do. He bought the Port Elizabeth terminal in New Jersey and rebuilt it from scratch to handle containerised cargo. The unit economics of this port were evidently better than those of its peers. The numbers were better because of savings in time and labour, and with that, the logistics revolution began.

Once ports retooled, the economics flipped:

- Loading costs dropped from $5.86 per ton to $0.16, a 97% reduction.

- Ship turnaround time fell from 72 hours to less than eight hours.

- Throughput per berth increased eightfold, collapsing trade friction.

What does this have to do with money? Shipping is simply the transfer of produced goods from one port to another. The internet allowed the transmission of information on a global scale. Much of it is standardised in the formats we consume —text, video, images. The media are the same.

But money? We use differing standards for each part of the stack. Even the crypto industry cannot agree on the standards and forms of money we use, which is why we have multiple L2s, bridging solutions, and a mix of stablecoins. It used to be a dollar on the internet. It’s USDT, USDC, USDC.e, sUSDe,sUSDs now. Make it make sense.

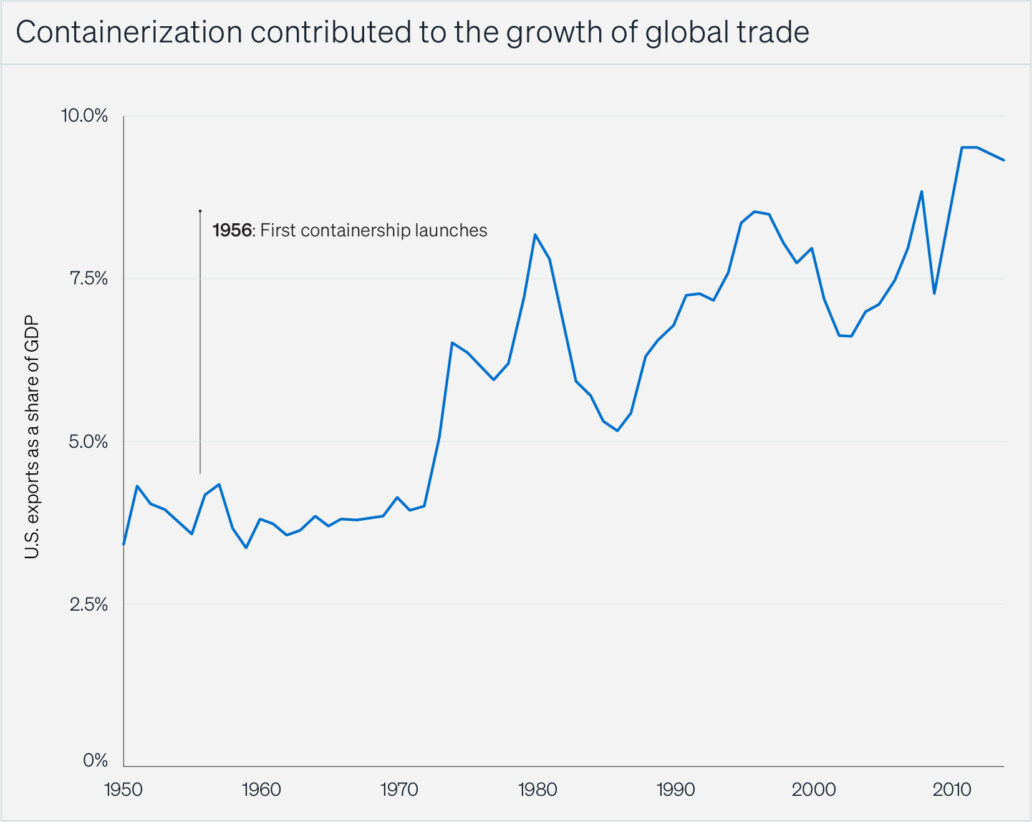

Stablecoins are where shipping used to be in the 1950s. The underlying technology works. Blockchains are faster than banking, much like steam engines are better than sails. But unless there is standardisation for the flow of capital, we may not be able to unlock the benefits they offer. Global commerce needs a shared language to emerge, much like containers did in the 1950s.

This standardisation of global money movement is the vision Plasma is building towards.

The Movement Tax

The Internet has standardised the spread of information, just as containers have standardised the spread of goods. Between HTTPS and SMTP, we communicated and consumed more information than at any point in time because the methods of transmitting it were standardised. However, that never quite happened with money. To understand why this matters, consider a simple remittance transaction.

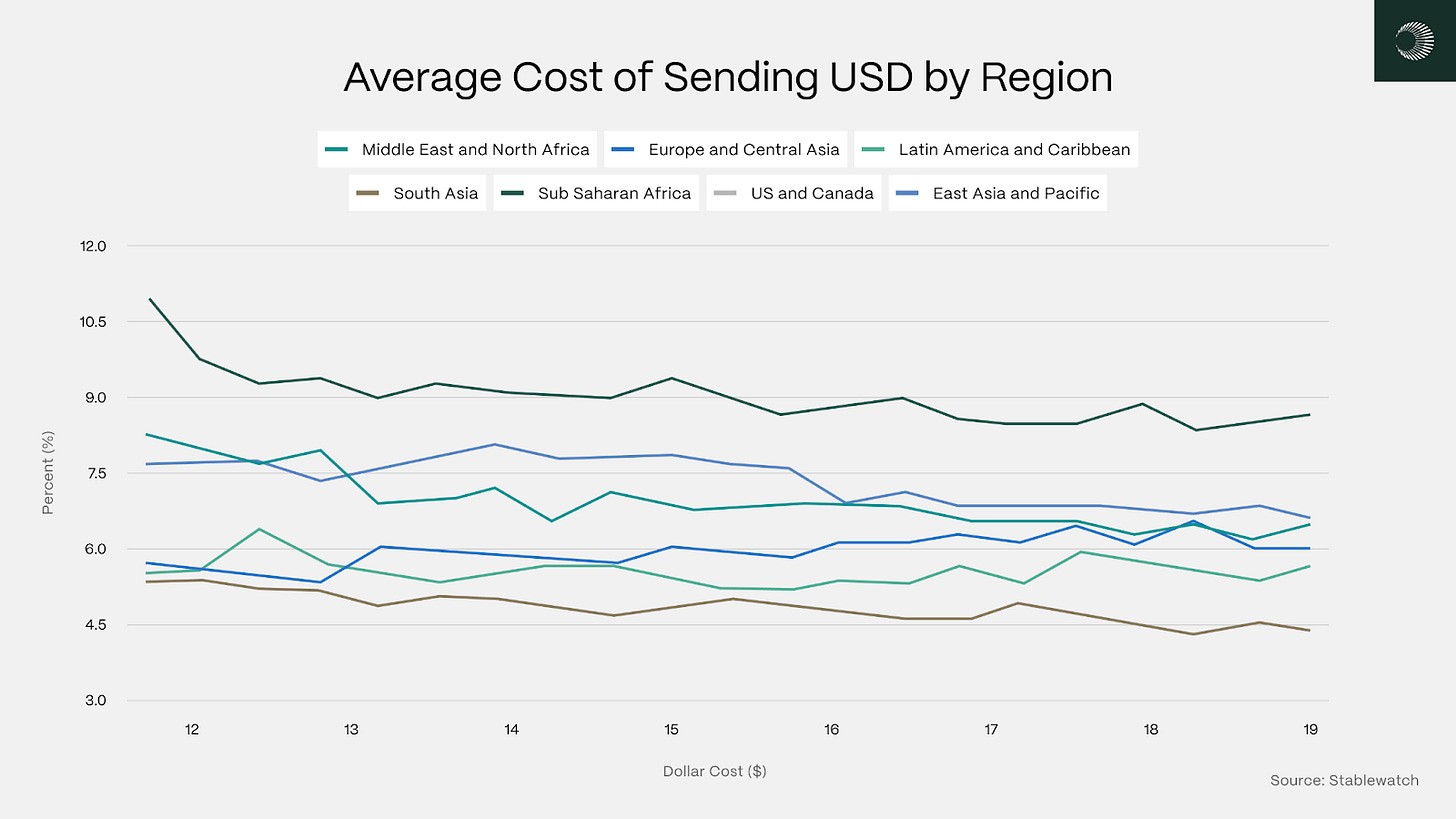

Let’s assume that a person transfers $1,000 from New York to Lagos every month. Usually, the transfer would incur a $45 transfer cost if done via SWIFT, and the sender takes that cost. The correspondent bank in Lagos would charge anywhere between $15 and $30 before settling it to the recipient’s bank. This is in addition to any forex costs that may be incurred. There is a 7% tax on the transfer even before it hits the receiver’s account. Add it up over the course of a year, and you are looking at $840 lost to intermediaries for updating ledgers.

Here’s where it gets interesting. According to a paper published in 2023, a 1% increase in the remittance flowing to a country can improve its Gini Coefficient by 2%. On the flip side, a 1% increase in the cost of remittance can reduce the amount sent to emerging markets by up to 5%. Most recipients in emerging markets are unable to use remittance slips as proof of income. Which means by nature, they are cut off from financial primitives like loans or credit cards from banks.

In 2010, the cost for remittance averaged between 7% and 9%. In 2025, according to the World Bank, that number has reduced to an incredible… never mind. The figure stays at 6.5%. Although solutions like Western Union, Wise, and Remitly have made massive improvements in how money moves, they are still a small chunk of the pie.

Stablecoins represent a natural alternative. With regulatory clarity from frameworks like the GENIUS Act, they’re becoming safe, compliant representations of major currencies. The cost of stablecoin transfers averages under 1% for any transfer size, regardless of destination.

The underlying infrastructure (of banks) remains isolated and out of reach for developers to build applications directly on. Individuals building remittance or transfer products on stablecoins assume the risk of compliance, regulatory interactions, and tax considerations themselves. This incurs additional costs if you are building in an emerging market like India.

Assuming global volumes of $800 billion and an average fee of 6.5% globally, stablecoin-based remittance businesses alone are looking at $52 billion+ in revenue to eat into. This is the opportunity subset for new primitives to emerge. Although stablecoins and payments networks have made considerable progress (much like shipping), the tools to standardise the flow of capital have not.

Part of the reason is the divergence in compliance policies and geo-specific user preferences. But what if these things were plug-and-play? That is the bet Plasma is taking. Before we go there, it helps to understand how money moves on the internet today.

Isolated Dollars

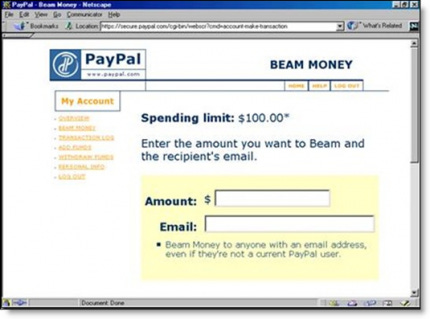

The internet got money online. Stablecoins explored what could be money on-chain. Both operate in isolated pools of capital that are restricted by geo-specific regulations. The digitisation of money arguably began as early as the 1860s, when Western Union used the telegraph as a mechanism for remitting capital. By the late 1990s, the likes of PayPal emerged to update archaic banking APIs to provide what the internet needed for transactions. Marketplaces like eBay needed a faster mechanism than cheques and bank wires to remit money – PayPal stepped in there.

PayPal itself didn’t make money digital. Credit cards were common at the time, as was the ability to process bank wires. According to its founders, at the time, PayPal’s biggest element of risk came from fraud. As early as the early 2000s, 1% of all transactions on PayPal were fraudulent, and this could kill the business.

So, they set up security systems that analysed the probability of a transfer potentially leading to trouble. By late 2001, that number was down to 0.037%.

All of PayPal’s value came from an underlying ecosystem of tooling that identified fraud and reduced risks for individuals transacting. In 2004, Peter Thiel would ring up a former roommate (Alex Karp) and build Palantir on the same methodologies.

Stripe did to global eCommerce what PayPal did for the US in the early 2000s. By the time the payment processor came around, debit cards were ubiquitous. However, the mechanism of accepting them from various parts of the world without bundling multiple APIs did not exist. In 2007, when Patrick and John Collison began work on Stripe, there was a far more pressing issue.

If you were a developer engaged in doing large volumes online, PayPal could restrict your access to capital for up to sixty days. That was the period needed by the firm to ensure there were no chargebacks. Stripe stepped in and reduced it to seven days, thanks to the rising use of credit cards.

What PayPal was for eCommerce in the early 2000s, Stripe was for developers building applications on the web in the late 2000s.

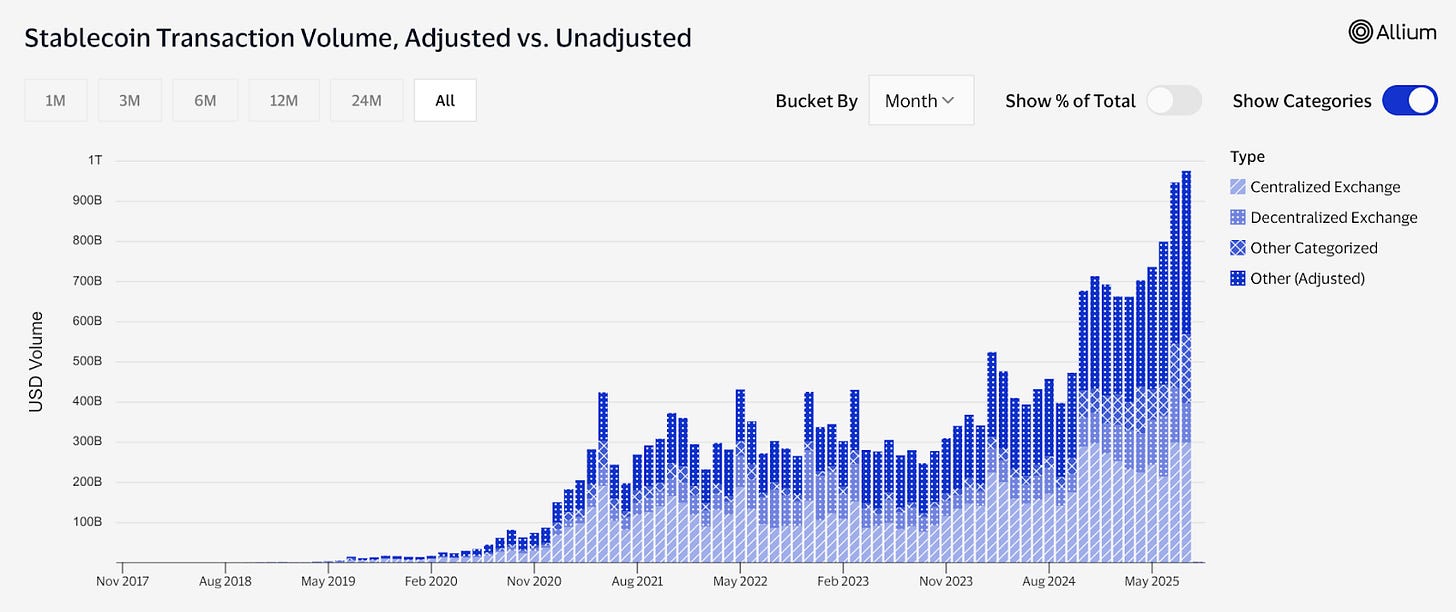

Stablecoins played a similar role in the rise of exchanges over the past few years. Instead of being payrails for marketplaces engaging in physical goods or developers, they focused on exchanges. According to data from Allium, half of all stablecoin transactions occur from a decentralised or centralised exchange. Only about 0.6% of stablecoin transfers are from retail users. Stablecoins emerged as banking rails for a crypto-native userbase, but the legitimacy offered by the GENIUS Act now allows it to flirt with going mainstream.

The challenge, however, is not with technology. It is the ecosystem surrounding it.

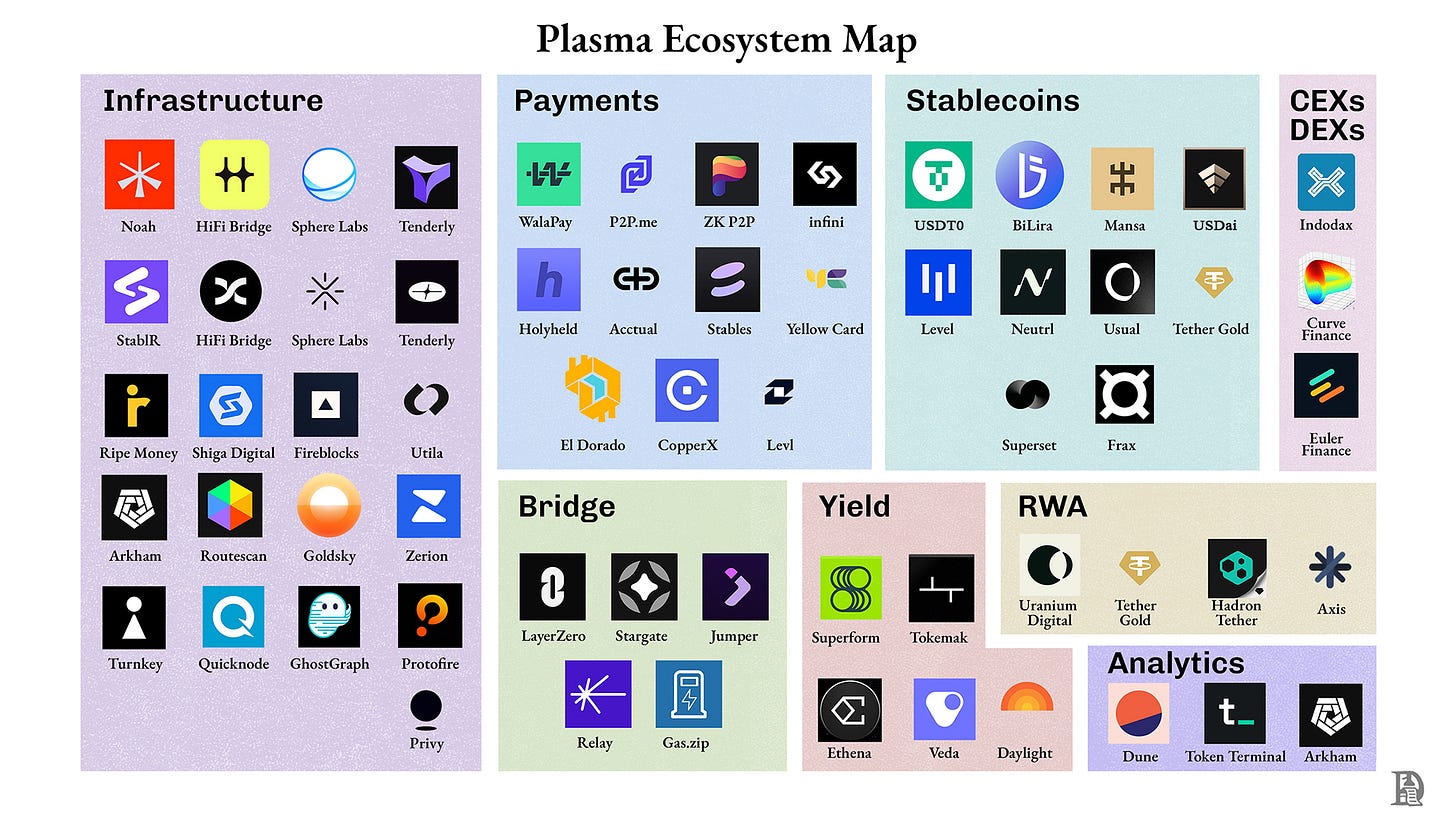

Unlike PayPal or Stripe, the tooling needed to vet, offboard, and enable transactions at the retail level has not evolved entirely. Both PayPal and Stripe were building on banking ecosystems that were fifty years old. Stablecoins, in contrast, are an eleven-year-old technology. And that means friction. For users, the friction emerges from the need to know how private keys and wallets work. Tools like Privy’s embedded wallets help abstract that complexity today for businesses, which means taking on compliance risks and fraud prevention. It also requires understanding how taxation works.

In the traditional fintech world, the tooling for this is aggregated. With stablecoins, that opportunity is wide open, but why has nobody built it yet? Part of the argument is that the liquidity (of capital, users, and apps) is not concentrated. The reason it is not concentrated, as seen with PayPal’s merchant liquidity or Facebook’s attention liquidity, is that blockchains today are general-purpose networks with no incentives for sectoral experts to come in and build.

When applications get large enough, they move into their own chain and ecosystem.

But what we create in the process are isolated ecosystems that require new tooling each time a network launches. That is why users are now left with a multitude of choices when it comes to stablecoins.

Cannibalising Money Legos

Stablecoins will soon do to global payments what Robinhood did to the stock markets – drive fees to zero. Payment networks will generate returns through yield on the dollars, but they have digital representations of it moving on-chain.

Consider USDH. Hyperliquid had signalled interest in wanting its own stablecoin under the ticker of USDH. Currently, the $5 billion+ that resides in Hyperliquid’s ecosystem earns zero yield for the exchange. At 4%, that comes to $220 million in revenue for Circle instead of Hyperliquid. Last week saw the cannibalisation of all that revenue (assuming users port over to the new coin) – as Native Markets won the bid for USDH ticker.

BlackRock and Superstate will manage the new stablecoin. Interestingly, Superstate will be using Bridge to manage the on-chain components, which in turn is owned by Stripe. There is no big conspiracy to point towards here. It is simply symbolic of how the payments ecosystem is evolving towards a world of no fees.

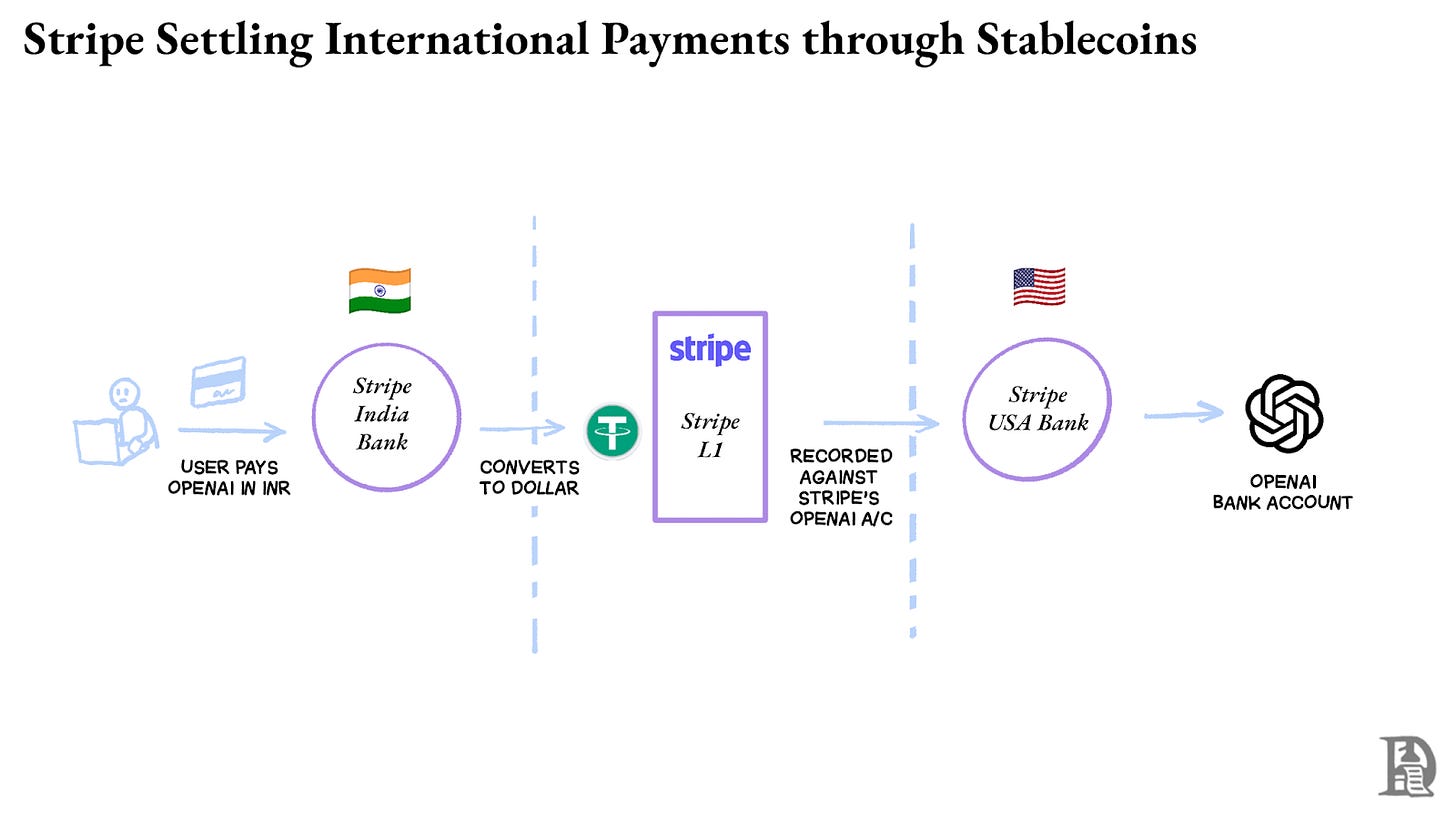

To understand how they may monetise, consider the transfer below for the payment of a ChatGPT subscription from a developer in India. In a hypothetical future, Stripe could circumvent SWIFT entirely by using its own L1 for transferring capital and using local stablecoin liquidity to convert the money to regional currencies.

The flow would look like this:

- Hold INR locally in its Indian bank.

- Net stablecoin-equivalent flows internally on its L1 ledger.

- Credit OpenAI’s U.S. account in USDT instantly.

This mirrors the netting strategies that international banks use, but with faster settlement and lower fees. Stripe is building something like a private port for its merchants. It is also designed to save on foreign exchange costs if the strategy scales. It mimics conventional remittance networks, such as those used by TransferWise. In other words, Stripe is moving further down the stack, where banks once existed, and replacing them with its own blockchain.

Circle has a similar approach with its blockchain – Arc. Instead of having users transact in dollars, it allows regional payments (in, say, Naira or Rupee) and captures fees on the foreign exchange spread. In some sense, most payment businesses perceive the cannibalisation of their core business as happening.

Visa and Mastercard see how stablecoins play a role in payments and have launched their own programmes to aid stablecoin-denominated debit cards.

The incentives for each of these products are to create walled gardens where internal suites of tools are offered. But what if developers could step in and build legos that catered to specific sectors or geographies? The thesis is that instead of building context on each market, the network is better off focusing on creating an open ecosystem that allows people to come in and build tools.

For instance, in India, when you subscribe to a publication (on Substack), you may not be able to use your locally issued card due to laws involving two-factor authentication. To allow any stablecoin flow would require having that context. Stripe has historically struggled to establish that context, thereby losing market share in the region to local competitors.

Plasma’s belief is that building distribution and an open ecosystem with such context being delivered by developers is the best way to push finance further on the web. Let me explain how it works.

The Neutral State

Remember how I previously mentioned that Peter Thiel once used learnings from PayPal to help Palantir launch? He also has a role to play in this story. Peter Thiel was one of Plasma’s earliest angel investors. His conviction was high enough to do a follow-on cheque from Founder’s fund in a strategic round. Bitfinex and Framework Ventures joined forces in May of this year. In July, the network raised an additional $50 million for its war chest from a 10-day token sale that saw some $373 million in demand.

But what is all that money and expertise for?

Plasma’s focus is on building the operating system for global money transfer as a neutral infrastructure provider with easy mechanisms to on-ramp and off-ramp. It uses a modified mechanism of Hotstuff, the PoS algorithm that is used by chains like Monad and Sei. Validators stake XPL tokens, the native tokens of the Plasma chain, to participate in validation and earn XPL rewards. For users, payments feel instant and free. Users never touch XPL.

In fact, this is what a payments infrastructure with gas assets abstracted could look like.

But remember how McLean once had to build a port alongside the containers to prove standardisation works? Blockchains are in a similar phase. We can have zero-fee transfers. We can have wallets abstracted. But for stablecoins to make a dent, we will need the ecosystem around them. Ultimately, this is where Plasma is focused. On making money legos plug and play.

Every time capital changes hands, a complex stack of software plays a role in the back end. It can range from where the capital is stored (wallets) to how legitimate it was (Chainalysis) to how it generates yield. The machinery tends to be integrated in traditional finance but heavily guarded. Imagine you had to pay a $20k subscription fee to a compliance provider, keep a balance sheet of a million dollars at the bank for API access, and a further million with a liquidity provider to run an on-ramp. It heavily restricts the number of individuals who can build on-ramps.

If you are a fintech founder building on DeFi rails today, you are not just battling the challenges of on-ramping or educating users about wallets. There are issues in finding composable lego blocks that can be used. For instance, you may allow users to buy gold from an issuer on Base. Your source of yield may be on Solana. The data pipelines keeping track of your users’ portfolios may not be compatible with a compliance provider’s needs.

When the user wishes to offramp, there may be no debit card issuer for the L2 being used for the transfer. Or perhaps any yield generated could be lost to the off-ramping costs. Users will not be interested in marginal improvements in yield when considering the risks that come with moving assets on-chain. This discounts the regulatory landscape that exists for crypto, especially in emerging markets.

For fintech founders, the challenge is not just regulatory. It is navigating the complex web of toolsets that operate in isolation today. Instead of obsessing about what users need or focusing on distribution, founders are caught up in the hellfire of the changing landscape of tools for building products. There are no container boxes. Each of the components needed for these primitives is in different shapes and sizes, and when we try to stack them together, things often break.

All of this is excluding the fact that the rails we need to interact with traditional finance don’t exist as things stand. Tools for accounting, payment with debit cards, geo-specific compliance checks, or distribution do not exist at scale. There is no WeChat or WhatsApp for crypto-native money. There are a multitude of applications that are in isolation. This happens partly because our focus has been on developing the technology rather than on distribution.

This challenge scales even further when you consider on-chain native businesses. A business could have millions of dollars in revenue accrued in stablecoins, but no credit line from conventional banks, as banks do not treat stablecoins as real revenue. Or even worse, they would have received payments in stablecoins, and the taxation of that income is different in some regions. How do you create tooling for such situations? You go ahead and allow developers to build each of these components, and allow markets to determine which part of it has the most demand.

The Plasma thesis is that the baseline infrastructure itself can stay neutral. The focus should be on the upstream network of businesses built on top of it for the economy to steadily shift on-chain. Why does this even matter? Because capital density is what usually unlocks network effects. Networks like Ethereum and Solana today have a massive amount of developer tools that look inward – towards the crypto industry. And since the TAM of users doesn’t expand, these tools cannibalise one another by being forced in a race to the bottom on pricing.

Plasma’s approach is to remain neutral and focus on payments as a use case, while allowing the market to determine which sector or geo-specific tooling will have the most value in an open ecosystem that enables developers to build fintech apps at a global scale.

But then, where does the moat come from? Our understanding is that it will be a function of liquidity. If a substrate can bring off-chain financial primitives to interact with on-chain representations of value (like USDT), then it will eventually see the highest density of capital flows. Currently, stablecoins are a commodity across chains. Owning the chain where the most liquidity resides will become a moat. And that is what Plasma is going after.

This is akin to how operating systems work. Apple or Android is valuable because they have the most users. And they have the most users because they have the highest number of developers. It is a loop that feeds on itself. Ultimately, what will differentiate chains will be their ability to distribute themselves among developers and penetrate niche, untapped markets.

But what is in it for the user? Currently, stablecoin transfers are cheaper and faster than conventional payment networks, but they are also throttled by liquidity. If Plasma and its network of tools can deliver on its ecosystem, then it will be able to scale to where traditional finance is. Consider that today, a large business managing even $1 billion in on-chain volume may not be able to off-ramp it in a region like Vietnam or India, where exports are a core part of the economy.

A world where Plasma dominates is one where the liquidity to move transactions of that size exists.